Hi friend,

While on my residency at MacDowell, a super-special-one-of-a-kind-thing happened. Did I win the lottery? In a way. A few days before my friend Catherine was all packed up to leave, she conspiratorially whispered, “Have the librarians make you a box.”

“A box?” I imagined a bento box, or – due to the air of mystery in Catherine’s tone – a magician’s assistant lying in a cedar box with her head & feet poking out as she was being cut in half. Reader, I imagined a lot of things. It’s kind of my thing.

Catherine explained that if I told the librarians a few interests relating to my work (AKA consciousness, the mind, brain anomalies & illnesses & disorders, patients who had awoken from comas, & such) that they would curate a box of books, articles, & even audio/video related to those topics. Most of the books would be plucked from the James Baldwin library on site & so the authors would be former MacDowell fellows themselves. Well friends, I won the lottery. A more dynamic bento box has not existed. Oliver Sacks Hallucinations was in there. Of course! How had I not thought of Sacks in my research for this novel? As was an article about T La Rock, one of the pioneers of Hip Hop, who suffered a brain injury that led him to “forget he’d ever been a rapper at all.” Too, an utterly strange book called About Trees by Katie Holten which “considers our relationship with language, landscape, and perception.”

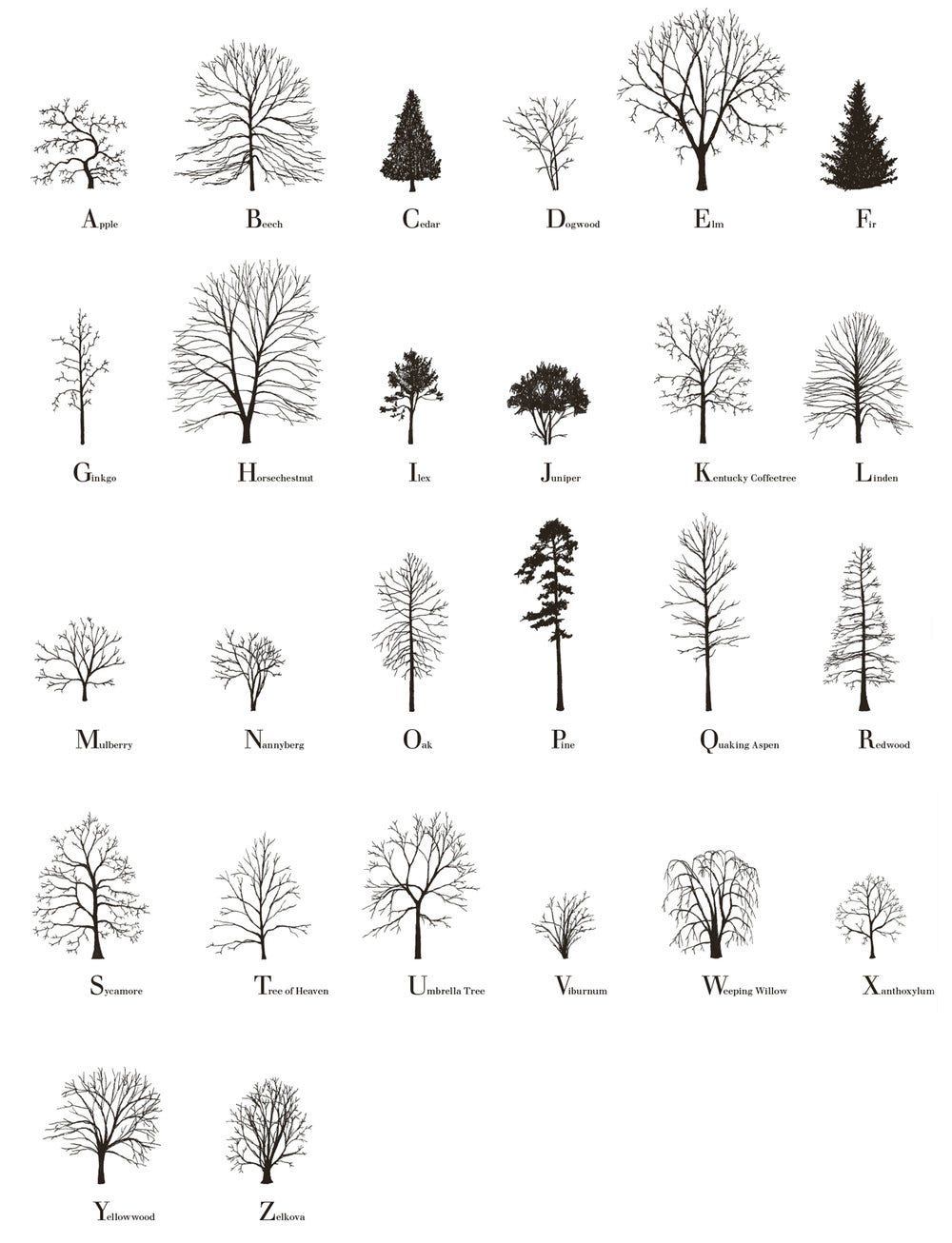

The book included an invented Tree Alphabet & even some translations of meaningful passages about language, landscape, & perception written in the tree alphabet. I was transfixed. One essay, All the Time in the World by Rachel Sussman, particularly gripped me. Since 2004, Sussman has been researching, working with biologists, & traveling the world to photograph continuously living organisms 2,000 years & older, culminating in a project aptly called The Oldest Things in the World.

In her essay Sussman mentions The Senator, one of the oldest cypress trees in the world. When it collapsed & died, engulfed by flames, it was 3,500 years old. What struck me deeply was her understanding of each life form as an individual, including The Senator. She writes, “When I got the film back, I knew I had missed my mark: there were some interesting compositions, but I hadn’t captured the spirit of this remarkable being. I was coming to see my subjects as individuals, and as such I wanted to make portraits of them rather than landscapes.”

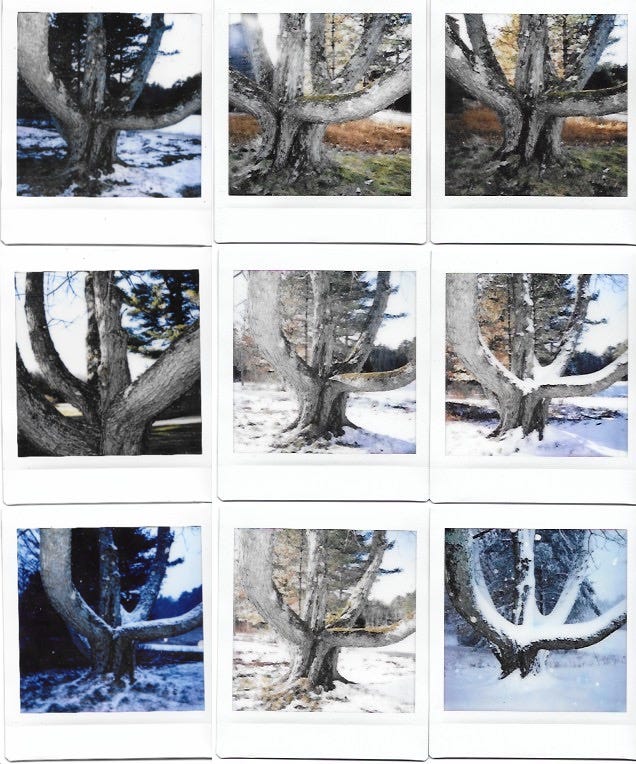

As I pored over About Trees, I was overcome with love for The Senator. Too, I felt overcome by fate. Was it serendipity that over the last few weeks I had been captivated by a single tree, the one in front of the library, so much so that I regularly photographed her on my breaks between novel writing?

I understood what Sussman meant about her images needing to elicit portrait versus landscape. In my nine snaps, I see nine different incarnations of one being. She is in different outfits, bears different expressions, emanates different mood states. She is not any tree. She is this tree. She is wholly herself. I first approached her because I loved her open arms. This month, back at home in Brooklyn, I decided to write Colette Lucas, the wonderful librarian at MacDowell, & ask about my old open-armed friend. I felt a bit twee sending a late-night follow up email about a tree. But Colette responded with seriousness & kindness, “The gardeners referred to that particular tree as the ‘basket maple’ because of its shape.” Ah, yes, open arms, open basket. I also learned that this was also a favorite tree of a previous gardener. I like to think that’s because this basket maple has stage presence, a lot of zhuzh. Colette added, “it always drops the first red leaf of the season.” She knows things. She says things. In her own way.

In a way, Sussman saying that she wished to take portraits of landscape makes me wonder if what appear to be portraits of humans aren’t actually landscapes. Have you ever heard of Nancy Floyd? She took a selfie every day for 40 years. Observing Nancy over time, I can’t help but see nine landscapes. I see a humanscape whose shape shifts, whose background hardens or softens, whose life-force is an expression of a terrain as much as of an identity.

• Our April ISL session is now taking applicants! Our Visiting Faculty are J Wortham, Franny Choi, Angel Nafis, Taylor Johnson & myself. Jaws, commence dropping! This is your official invitation to let this upcoming National Poetry Month be the season you devote to yourself & your work – whether your work is poems or a musical or a novel or just trying to be creatively present in a different, daily way. Come on in, the water’s fine. Plus, your creativity deserves you.

• This person’s burst-wide-open-heart continues to shape my own heart

• There is something profoundly sweet about seeing wives sing to each other

• Photographs of love & loss in the UK’s first AIDS ward

• I am very moved that this book is now in the world, edited by the truly singular Aracelis Girmay

• Such joy that my friend Kaveh shared with me this poet I’d never heard of & now can never shake

• This Radiolab episode had me thinking about striving for good & how we can sometimes get tangled in our own darkness along the way

A space where I interview an artist I admire in three questions

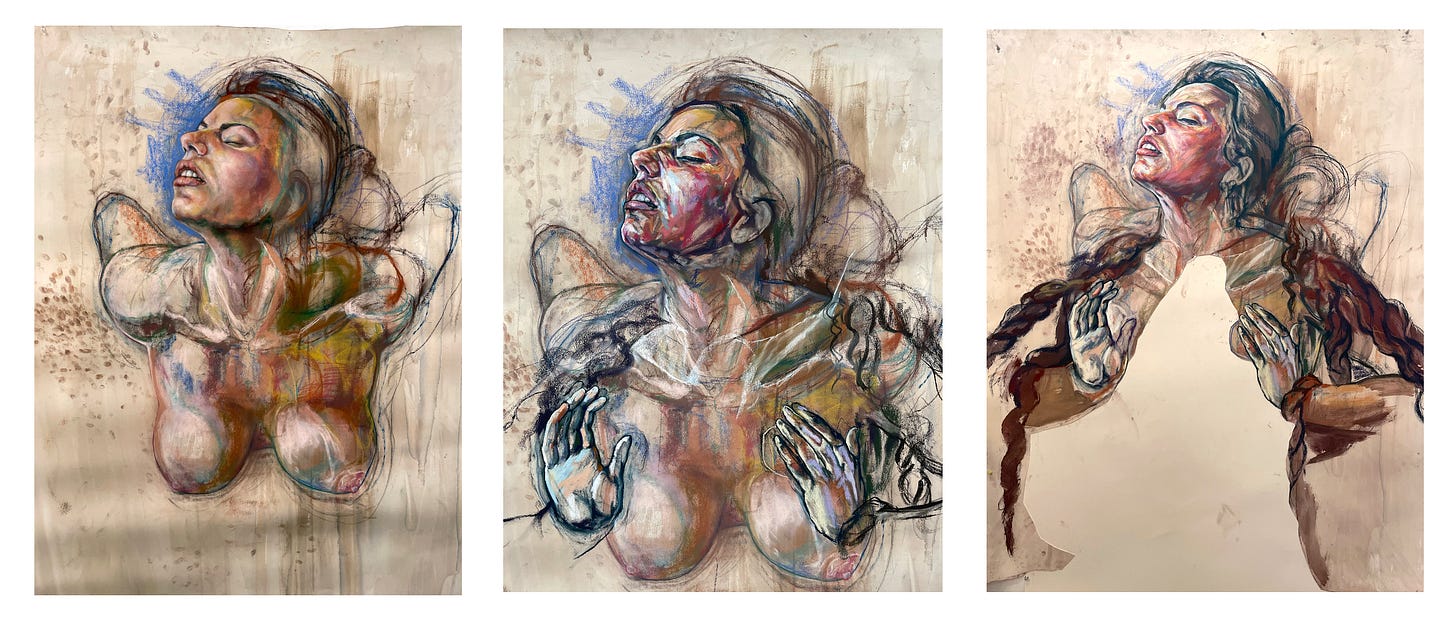

Today’s interviewee is visual artist Ghislaine Fremaux. I met Ghislaine in high school & somehow we have stayed connected all these years, supporting each other’s work & staying awake to each other’s grapplings. She visited ISL this past October.

1 • On Instagram you posted that you are reworking a self-portrait you made when you were 24 now with your partner. What has this process been like?

I drew this self-portrait when I was in graduate school in 2011. It was a private sort of picture. I remember photographing myself as I pressed my body against a tall, wheeled stool.

I know now that it had something to do with belonging to myself, holding myself (up), something like being my own love, my own lover.

The drawing came quickly. In critique, my professor said he didn’t care for the “exaggerated features”. I remember I had no idea what he was talking about. The drawing showed in New York in the winter of 2012 and was shipped back to me in January 2013. I never opened the box.

When I moved to Texas in 2014, the box moved with me, and it lived almost ten full years in my garage, untouched. Last year, it occurred to me that Lando and I could use it as a point of departure or raw material for new work.

When I pulled the drawing from the box and unrolled it, I was surprised it was undamaged. Lando seemed surprised by the piece, too, but for different reasons. To begin work on the drawing, I found the reference photo from 2011. I think I made the first pass, retuning the face. Lando came in soon after.

Drawing collaboratively, at least for Lando and me, is an argument – a good-faith argument. Each of us is making claims in turn. As we rotate in and out of the drawing, every time we must decide if we believe the claims the other person has made. If you believe them, you corroborate them, amplify them; the claim becomes fact, and the rest of the drawing will follow from it. If you don’t believe them, you rebut them, erasing or rephrasing them.

This face spent a long time in the weeds of the argument, each of us unable to place trust in what the other one was seeing and reporting. I think I felt like the face Lando kept turning up was too easy to look at to be mine. When I could at last recognize something like truth in his account of my face, it felt good.

For me, reworking this drawing with Lando has been moving. I remember what was happening in the life of the person who made that drawing. I remember how the seeing-of-me was different then than it is now. It feels like my partner’s hands and my hands, now 36 years old, are retrieving and caring for and making newly whole the me from 2011.

We do not disparage the original drawing at all. The 24-year-old person who made and is represented in that drawing was real, is real, and is still there.

But it feels like we are giving her clean air or working lungs now.

2 • If you had to eschew the word “visual artist” for what you are or for what you do, what word might you call yourself? What name might you give for your type of creating or – if it resonates – seeking?

Perhaps I am a diver. I hold my breath (and I do, literally) and throw myself into the boundless space of a magnified photograph. I am looking for something in those depths but I am looking so closely I almost cannot see. The thing I seek cannot be grabbed, cannot be ‘had’. But I dive, and when I think I’ve seen it, I rush to the surface and I tell what I saw. I breathe and then I dive again. I keep diving and rising and telling until I don’t see anything more. By then, without knowing, I have told a story.

3 • What verbs, or actions, are important to you in your art-making? What verbs constitute your making? Which verbs could you not live without?

Words that taught me how to fall all the way in love with process: Wringing, mining, picking. Incising, striking. Tearing out, ripping out. Stitching, knitting, weaving.

Honor it. Free it up. Make it turn. Put bones in it. Make it able to move, able to walk. Make it real. Make it true.

Thank you for being here & for reading, friend.

May you see yourself as a landscape, ripe with changes & tall with birds. May you see yourself as a humanscape whose hidden music is a valid clock.

May you converse with your own face & body & spirit, re-belonging to yourself.

May you meet all of nature as individuals; not a tree but that tree, not a raccoon in the neighborhood trash can but that raccoon in the neighborhood trash can, with its own whims & personality & schedule; not the sky, but the sky right now - untrappable, never frozen, a bandit with leaky pockets spilling & spilling.

With ample maple syrup,